OSWALD GOT A GUN

The final act of the tragedy began to unfold in March 1963. Oswald, fearful of further interrogation by the FBI, moved to 214 West Neely Street in Dallas. This apartment afforded Oswald, for the first time in his life, a small space, not much more than a closet, a study to hold his books and papers. His little library was a personal sanctuary that even Marina could not enter without permission. It was from this tiny cubicle that Oswald, the overbearing megalomaniac, planned the attack on General Walker.

Major General Edwin A. Walker was a decorated veteran of World War 2 and the Korean War. Walker, by the end of his thirty-year career in the Army, became disillusioned with US foreign policy and attempted to force his political views on his command, the 24th Infantry division, based in West Germany. Walker was relieved of this command by John F. Kennedy pending investigation of his activities and critical statements directed at prominent Americans, including President Eisenhower.

Walker resigned from the Army in November 1961 because he..."must be free from the power of little men who, in the name of my country, punish loyal service to it.” Walker's post-Army career further developed his segregationist mindset. He was a pivotal spark in a riot at the University of Mississippi, in October 1962, during the enrollment of its first black student, James Meredith. Two men died in the violent fifteen-hour melee and Walker arrested, charged with insurrection and seditious conspiracy. However, a federal grand jury failed to indict him, and the charges dropped.

In the middle of March, Oswald, in addition to surveillance of Walker's residence, continued to demand Marina's return to the Soviet Union and, into this quandary of marital discord, stepped Ruth Paine. Ruth wrote to Marina and stopped by to visit their new apartment, she reiterated her offer of housing in exchange for Russian lessons, a chance for Marina to stay in the United States, and an opportunity to have her second child in a stable household. Ruth Paine was Marina's only friend, a friendship Oswald, as lord of his household, allowed. Oswald was too busy for Ruth Paine. He sat in his little office and filled in the name of A. Hidell on an order coupon from Klein's Sporting Goods for a 6.5 mm Carcano rifle.

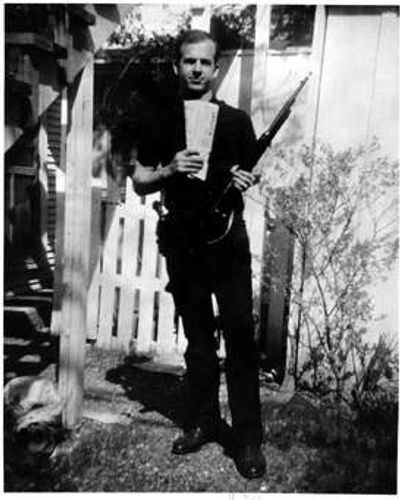

Oswald's rifle, along with a previously ordered Smith and Wesson .38 revolver, arrived on March 25. The following Sunday, March 31, according to Priscilla McMillan, was a sunny day and Marina, busy hanging diapers on the clothesline, was startled to see Lee, dressed all in black, holding a rifle and some newspapers in his hands. He also had a camera. She took two pictures of Oswald in his urban guerrilla uniform.

The Backyard Photos, as they became known, were (and still are) a source of contention among the assassination research community. Oswald exclaimed, shown the photographs following his arrest, "the photos are fake," his head superimposed on someone else's body. The conspiracy advocates produced photographic experts that claimed the pictures were, indeed, fake. However, other credible photographic experts have examined the pictures and confirmed their authenticity. The answer to this puzzle comes from two sources. Marina, in her testimony before the Warren Commission and the House Select Committee on Assassinations, admitted taking the photographs. Additionally, Oswald gave a signed a copy to George de Mohrenschildt, the signature verified as Oswald's, and probably the most conclusive evidence to support the validity of the Backyard Photos.

A video of commentary suggesting photographic trickery

The "Backyard Photo" taken March 31, 1963, by Marina Oswald

ASSASSIN, IN TRAINING

On April 1, 1963, Oswald received some bad news from Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall, the only job he ever liked was at an end, and his last day was Saturday, April 6. How this affected Oswald's emotional state is difficult to interpret however, there can be little doubt the job termination accelerated a perverse chemical reaction in his brain and produced an assassin. Oswald, on the night of April 10, less than a week after his dismissal, positioned himself in the alley behind Walker's house and took aim at the general. Walker, seated at his desk, with the window blinds drawn up, was an easy target for the sniper hidden in the shadows.

Marina told the Warren commission, to the best of her memory, Oswald left around 7:00 or 7:30 that night. She found a note, written in Russian, details of what she should do if he did not return. She had no idea what he was up to, but, when he finally arrived home about 11:30, she pressed him for answers. Oswald admitted shooting Walker and turned on the radio for news of the event. Marina was furious. She asked, "Where is the rifle?" Oswald laughed, he had hidden the rifle and "would go back to get it in a few days.” Marina insisted he destroy all the evidence, the maps, the pictures of Walker's house, his notes, anything that might be incriminating should the police place him under arrest.

Oswald discovered the next morning the bullet had missed its target. Dallas police had no suspects and the bullet, damaged beyond recognition, yielded no useful information. In fact, what had saved Walker's life was a piece of the window rail. The rail was probably not visible in Oswald's 4X scope, and it offered enough substance to deflect the bullet just over the intended victim's head. Walker told the police he heard a loud report, felt some debris in his hair, and a small bullet fragment landed on his arm.

Here is a link to General Walker's comments following the murder attempt on his life.

Many in the conspiracy community do not believe Oswald committed this crime against General Walker however, the evidence is overwhelmingly one sided. Marinas's testimony, the most important evidence, defined the truth against Oswald. Conspiratorialists claimed she faced threat of deportation and her testimony reflected what the Warren Commission expected to hear. However, her testimony before the Warren Commission does not support this claim. While her initial interviews with Dallas police and the FBI were probably strained and coercive, Marina, by the time of her Warren Commission testimony, knew her place in America was secure. She received substantial contributions from the American people, hired a business manager, and had no reason to lie.

Marina, following the attempt on Walker's life, fearful of Oswald's arrest, suggested he leave Dallas for New Orleans, his birthplace, where he still had some family. Oswald left Dallas by bus on April 24 and began, what would become, another bizarre period in his young and disturbed life.

Major General Edwin A. Walker, US Army

THE BIG EASY

On April 25, 1963, the young Marxist revolutionary arrived in New Orleans. He stayed with his aunt and uncle, Lillian and Charles (Dutz) Murret for a two-week period while he looked for work and an apartment. He spent a considerable amount of time researching his family history; he called every Oswald in the New Orleans phone book until he located his father's sister-in-law, Hazel Oswald. Oswald paid his Aunt Hazel a visit and they discussed family, she gave him a picture of his father, which was not among his personal belongings after his death, evidently lost or discarded.

Oswald was successful in finding work and an apartment. Two weeks after his arrival in New Orleans, the Reily Coffee Company hired him as a general laborer, a greaser, and an oiler of the coffee machines. He began work on May 10. Oswald then enlisted the help of a friend of his mother, Myrtle Evans, in the hope of finding an apartment near his new job. They found an apartment on 4907 Magazine Street for sixty-five dollars per month and he phoned Marina to tell her the news. The next day, Ruth Paine, Marina, the children, and all of the Oswald's meager belongings were loaded into Ruth's station wagon for the five-hundred-mile trip to New Orleans.

Marina was not pleased with her new apartment, she found it to be ugly and infested with roaches. Our young couple began their life together in New Orleans under a stressful and caustic atmosphere. Marina wrote to Ruth Paine shortly after Ruth's return to Irving, "I feel very hurt that Lee's attitude toward me is such that I feel each minute that I bind him. He insists that I leave America which I don't want to do at all." Marina told Ruth that Lee did not love her. Oswald reverted to his old demeanor, their arguments were volatile, but, as Vincent Bugliosi wrote, Oswald was no longer physically abusive due to her advanced pregnancy. Our young Marxist was doing equally poorly at work.

From the first day at Reily Coffee, Oswald harbored an indifferent attitude towards his work. Charles Le Blanc, given the task of training Oswald the specific duties of his work, told the Warren Commission “Oswald was just one of these guys that just didn't care whether he learned it or he didn't learn it." Le Blanc went on to relate Oswald's tactic of disappearance, he frequently left his duties and, when questioned about his whereabouts, simply stated, "Oh, I've been around." On several occasions, Le Blanc found Oswald next door at the Crescent City Garage and, as the garage owner, Adrian Alba, testified, "Many of the Reily employees felt Oswald spent more time in the garage than in the plant." Alba explained to the Warren Commission that Oswald's interest in the garage, aside from free coffee, was the large collection of gun magazines in the office area.

Two weeks after beginning work at Reily Coffee, Oswald wrote to Vincent Lee at the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, based in New York, requested formal membership, and a charter to open a branch in New Orleans. As Vincent Bugliosi wrote, Oswald wanted to lead a group in the fight against the foes of his new hero, Fidel Castro. Oswald ordered one thousand handbills from the Jones Printing Company under the fictitious name of Lee Osborne, for which he paid $9.89. In addition to the handbills, Oswald ordered five hundred copies of an application for membership and three hundred membership cards for the projected New Orleans chapter of FPCC.

Oswald's own membership card in the FPCC, New Orleans branch, is an indication of Oswald's inflated perception of his own greatness. It is also the source of some amusement. Oswald signed his own name on the card and directed Marina to sign the name of "A.J. Hidell" above the space "Chapter President." Marina asked who Hidell was, convinced it was nothing more than an altered form of Fidel, and laughed in his face when he admitted the need for another signature to create the appearance of a large organization when, in fact, it was a revolutionary movement of a single member. Marina, as she told the Warren Commission, agreed to play her husband's silly game and signed the card.

LHO handing out leaflets for the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, New Orleans Chapter.

EL PRESIDENTE

By the summer of 1963, Oswald was in full street agitator mode. He handed out pro-Castro leaflets on Sunday, June 16, at the Dumaine Street Wharf, the pier of the aircraft carrier, USS Wasp. The officer of the deck observed Oswald with suspicion and summoned the Port Authority police to investigate the young miscreant. Oswald, informed he could not distribute any literature without a permit, decided to leave rather than face arrest.

Oswald had no success recruiting members to FPCC and his marriage was foundering, a continual succession of abuse, assault, and reconciliation. Marina, alone and pregnant, afraid of being forced to leave the United States, was relieved to get a letter from Ruth Paine containing an invitation to live separately from Oswald. On July 19, Oswald received news the Reily Coffee Company no longer required his services and, a few days later, he filed a claim for unemployment benefits. Once again, poor work performance cost him another job. He allowed his personal appearance to decline. He was spiraling out of control.

Marina, as she told the Warren Commission, observed that everything Oswald was doing during this period centered on entry into Cuba. Oswald was building a resume of political activities friendly to the Cuban government. On August 5, he walked into a clothing store run by Carlos Bringuier, a Cuban lawyer who emigrated after the revolution. Bringuier was the New Orleans delegate to the anti-Castro organization, the Cuban Student Directorate, and Oswald indicated to Bringuier that, as a former marine, he was eager to help the cause of the Cuban exiles. Oswald returned the next day and left his Marine Corps manual in Bringuier's store. A few days later, Bringuier got word of a pro-Castro demonstration a few blocks away on Canal Street.

Bringuier and two associates approached the street demonstration. Bringuier was shocked and angered to find Oswald handing out pro-Castro leaflets. A scuffle ensued, someone pushed Oswald, his leaflets taken and thrown into the air, and people in the crowd shouted at him, "Traitor, go back to Cuba!” Police arrived at the scene and placed Oswald and the three anti-Castro Cubans under arrest. Bringuier and his two associates paid twenty-five dollars each, pending their court appearance the following Monday. Oswald, financially embarrassed, unable to post bail, spent the night in jail.

On Monday, August 12, Oswald entered a guilty plea to the charge of disturbing the peace and paid a ten-dollar fine. However, the court date had an unexpected result that pleased Oswald, he learned that WDSU-TV had an interest in his activities, and, on August 16, Oswald left word at the station of another pro-Castro demonstration at the Trade Mart, located in a busy part of downtown New Orleans. Oswald and two hired lackeys passed out leaflets for the television audience.

Here is a link to the television footage of Oswald handing out leaflets and his comments following his street demonstration.

Here is a link to Oswald's radio interview with William K Stuckey. Oswald, at times, appeared eloquent and, at others, appeared to ramble without answering the questions. He openly lied to some questions and, remarkably, his answers sounded like what his mother, Marguerite, said in her post-assassination interviews.

Fidel Castro with ever-present cigar

LET'S GO TO CUBA!

Oswald, consumed by the idea of going to fight for Fidel and help free the Cuban people from 'the strangle hold of imperialist America,' came up with an interesting and amusing plan. Around the third week of August, he informed Marina they would get to Cuba by plane, seized at gunpoint by himself and his pregnant wife. He planned to buy tickets under separate names, Oswald in the front of the plane, Marina seated in the rear and, as Oswald ordered the pilot to fly to Cuba, Marina would keep the passengers at bay. Marina asked, "Do you really think anybody will be fooled? A pregnant woman, her stomach sticking way out, a tiny girl in one hand and a pistol in the other?” She was not going to take part in a hijacking of a commercial airliner. "Only a crazy man would think up something like this," she said.

Oswald knew there were no flights from the United States to Cuba, but there were flights from Mexico City to Havana and, if he could obtain a visa from the Cuban Embassy, he planned to show the Cuban government his portfolio of work done in the United States on their behalf. He told Marina, "I'll show them what I've done for Cuba...and above all I want to help Cuba." Oswald set to work planning his travels to Mexico.

The devious little Marxist had a problem, what to do with Marina? Oswald had a plan. He had asked Marina to write to Ruth Paine, inform her of their financial predicament, and need of help. Oswald was counting on Ruth Paine, and she did not disappoint him. Paine wrote she could come to New Orleans and return Marina and June to Irving. Oswald then set up a financial plan for his trip. He was not going to pay the remainder of his rent nor pay any utility bills. He was going to pack Marina, June Lee, and all their belongings into Ruth Paine's car, dispatch them to Irving without giving Marina any traveling money, and simply leave New Orleans. On September 25, Oswald collected his unemployment check of $33.00 and boarded a bus for Houston.

Oswald's Mexico trip is a curious study. Many in the conspiracy camp believe Oswald was engaged in some type of espionage activity, a James Bond with a southern drawl. Sylvia Odio, a Cuban exile living in Dallas, testified before the Warren Commission that three men, two Cubans and one American, came to her apartment to solicit funds for the anti-Castro group JURE (Junta Revolutionary) on September 26 or 27. The American, described by Odio as about 35 years old, skinny, and about five foot ten inches tall, was introduced to her as "Leon Oswald." She testified this was the man arrested for the assassination of President Kennedy and his appearance on the evening news the night of the assassination caused her to faint. Oswald's involvement with anti-Castro Cubans was possible but, on the night of September 26, evidence suggests Oswald was on a bus to Mexico.

Oswald arrived in Mexico City on the morning of Friday, September 27 and checked in to Hotel Del Comercio at 11:00 am. He immediately went to the Cuban Embassy and applied for a visa. Oswald met with Sylvia Duran, a Mexican national with Marxist leanings, the consul secretary and presented his documents. He told Duran of his desire to travel to Cuba before continuing on to the Soviet Union. Duran explained to Oswald that he could obtain an "in transit" visa to Cuba provided he received an entrance visa to the Soviet Union first. Oswald became irritated and Duran sent for the consul, Eusebio Azcue, to clarify the requirements for a visa. Oswald said he was a friend of the Cuban revolution, founded the FPCC, New Orleans chapter, and suffered indignities in the United States while working for Cuba. Azcue, unimpressed with Oswald, was unyielding, no entry to Cuba without a Russian visa. Oswald abruptly gathered his documents, left the Cuban Embassy, and walked the short distance to the Russian Embassy.

Valeriy Kostikov, an officer in the consular section of the Russian Embassy, met Oswald in a waiting area and ushered the young revolutionary to his office. Oswald showed Kostilov his documents, records of employment and residency in the Soviet Union, Russian marriage license, FPCC membership card, and various newspaper clips of street agitation in New Orleans. As Oswald was retelling his story for the Russian consul, Kostikov, a colonel in the KGB, in addition to his consular duties, decided to turn Oswald over to counterintelligence officer, Colonel Oleg Nechiporenko. Nechiporenko's job was to determine if Oswald was CIA or if he could be a prospective Russian asset.

For Oswald, it must have felt like Moscow all over again but, this time, the KGB colonel figured him out. Nechiporenko asked Oswald why he wanted to go back to the Soviet Union after having voluntarily left with his wife and daughter. Oswald hemmed and hawed, changed the subject, and attempted to avoid the question because he had no acceptable answer. Nechiporenko broke off the interview. He told Oswald that, since he was an American, the visa must originate in the country of official residence, not in Mexico. Once again, Oswald gathered up his papers and left.

Oswald was still hopeful of approval of his visa. He had four passport photographs made, returned to a closed Cuban Embassy and, evidently, used Duran's name to gain afterhours access. Oswald presented Duran the four photos and, while she prepared the application forms, she asked for the Russian visa. Oswald lied to Duran; he claimed the Russians had his visa. A phone call to the Russian Embassy uncovered the truth and the Cubans unceremoniously ushered him out. Eusebio Azcue, in his testimony before the HSCA, said, "Oswald got very worked up...accused me of being a bureaucrat, and in a very discourteous manner, mumbled something to himself and slammed the door on his way out."

Saturday, September 28 was a day off for the Russian Embassy staff. All the consular officers were at the embassy that morning however, not for work, for volleyball. Pavel Askov received word a visitor was waiting to speak to a consul. Yatskov, not present at the previous interview with Oswald, met a distressed young American, a communist, a pro-Cuban, who feared for his life. Colonel Kostikov, quickly filled him in on the strange American. The Russians reiterated the visa policy to Oswald, there was nothing more they could do.

Oswald, distressed and on the verge of tears, pulled a handgun from under his jacket, put it on the desk, and exclaimed, "See, this is what I must now carry to protect my life." The Russians were stunned. Yatskov picked up the revolver, opened the cylinder, shook the bullets into his hand and put them in his desk drawer, then put the gun back on the desk. Oswald, with his hopes of fighting for the Cuban revolution now dashed, wept in disappointment.

Oswald endured another failure in his sorrowful life. He stayed in Mexico City for another three days and departed for Dallas on the morning of October 2. What he did and where he went during those three days remains a mystery. Some conspiratorialists claim either the Cubans or the Russians instructed him to assassinate President Kennedy. Some believe Oswald attended a party in company with Sylvia Duran, the Cuban consular secretary, where other pro-Castro Cubans convinced Oswald to kill the president.

Unknown man, mis-identified as Lee Harvey Oswald, seen entering Russian Embassy in Mexico City

Back in Dallas again

Oswald returned from Mexico on Thursday, October 3. He checked in to the Dallas YMCA and then called Marina at Ruth Paine's. He asked Marina to convince Ruth Paine to provide him with transportation to Irving but, Marina explained, Ruth was not home. The young Marxist, undeterred from his quest to visit his wife and daughter, regardless of convenience, hitchhiked to Ruth's house. Oswald, when he met Ruth, said he could not find work in New Orleans and decided to come back to Dallas. Ruth, the kind Quaker, told the Oswalds that Marina and June could stay with her as long as they liked. Oswald found this arrangement agreeable and, on Monday. October 7, on his return to Dallas, he found a room on Marsalis Street in the Oak Cliff area.

Oswald continued his search for work the week of October 7 and talked to Marina daily from the phone in the rooming house. He applied for work at Padgett Printing Corporation and favorably impressed the hiring manager. Oswald listed his former employer, Jaggars, Stiles, and Stovall, as a reference of his qualifications and Robert Stovall confirmed Oswald worked for him from October 1962 to April 1963. However, Stovall did not recommend hiring him due to behavioral problems which resulted in Oswald's termination. Padgett Printing notified Oswald they found someone else for the job.

Mrs. Mary Bledsoe, Oswald's new proprietor, overheard him speaking in a foreign language, a fact she found disturbing and, in addition to his bad habits and ill-mannered behavior, she decided to evict the young Marxist. Oswald told Mrs. Bledsoe, on October 12, he was leaving for Irving for the weekend but, to Oswald's disappointment, she told him not to return. He was out on the street after less than one week.

After spending the weekend at the Paine's, Oswald returned to Dallas and took a room in a house on North Beckley Street, under the alias of O.H. Lee. That same week, around October 14, Ruth Paine was having coffee with some neighbors and mentioned Oswald's difficulty finding work. One neighbor, Linnie Mae Randall, mentioned her brother worked at the Texas School Book Depository and she thought there might be a job opening. Ruth mentioned the job prospect to Oswald when he called that evening and, on October 15, Oswald met the superintendent, Roy Truly, and submitted an application for employment. Oswald, in his application, lied by omission about his past, failed to include any previous employment, and led Truly to believe he was a recently discharged marine with a good service record. Truly was impressed with Oswald's neat appearance and his frequent use of the word "sir" during the interview, he hired Oswald without checking his background and told him to report for work the next day.

Oswald became a father again on October 20, 1963, as Marina gave birth to Audrey Marina Rachel Oswald. Oswald, the ungrateful father, was indebted to Ruth Paine for her care of Marina during the pregnancy, care that Marina would not have received had she remained in New Orleans. He was content to allow Ruth to take care of Marina and two children, all without any monetary consideration. Oswald told Marina he wanted to get back together with his family and wanted to buy her a washing machine but, while he planned for the future, Oswald's past was about to catch up in the form of Special Agent James P. Hosty, FBI.

The FBI, according to Hosty's testimony before the Warren Commission, reopened Oswald’s case in March 1963, when Oswald's name appeared on the mailing list of the Daily Worker, the American Communist Party's newspaper. By the time Hosty tracked down Oswald to Elsbeth Street, then to Neely Street in Dallas, Lee and Marina were in New Orleans. On October 3, 1963, Hosty received information from the New Orleans FBI office that the Oswalds had left, two women with children in a station wagon with a Texas license plate, but Lee Harvey Oswald's whereabouts was unknown. Later that month, on October 25, Hosty received communication from the New Orleans office that Oswald had been in contact with the Russian Embassy in Mexico City. Hosty's break came on October 29, Oswald left a change of address with the New Orleans post office, an address on West Fifth Street in Irving, Texas.

On Friday, November 1, Hosty interviewed Marina, with Ruth Paine as interpreter. Hosty learned Oswald did not live in Irving but had a room somewhere in Oak Cliff. Ruth did not know the address where Oswald lived but knew he worked at the Texas School Book Depository, on Elm Street, in Dallas. Ruth informed Hosty that Oswald planned to visit that afternoon, around 5:30, and invited him to wait. Hosty declined. Oswald, when informed by Marina of Hosty’s visit, became enraged but, to Ruth Paine, who knew nothing about the attempt on General Walker, his trip to Mexico, and attempt to defect to Cuba, Oswald put on a mask of indifference. Oswald told Marina, if the FBI man ever came back, she was to get his license plate number and identify what kind of car he drove.

Hosty, while on his way to Ft. Worth, returned to speak to Marina on Tuesday, November 5. He wanted to find out if Ruth had obtained Oswald's address in Oak Cliff and Marina, as instructed by Oswald, wrote down the license plate number of Hosty's car. As a feud developed between Oswald and Hosty, the FBI office in New Orleans transferred the case back to Dallas in an age when information exchange took days, even weeks. In fact, the case file on Oswald from the New Orleans FBI office arrived in the Dallas office on November 21. Hosty took no further action in the case until November 22, 1963.

The second weekend in November 1963 was a three-day weekend, Monday was Veterans’ Day, and Oswald enjoyed Ruth Paine's hospitality, free of charge. Oswald asked Ruth Paine if he could use her typewriter and spent part of the weekend writing to the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C. Oswald, according to Vincent Bugliosi, complained in his letter about the treatment he received at the Russian Embassy in Mexico City and requested notification, as soon as possible, about his visa application approval. Oswald, as late as mid-November 1963, still maintained hopes of traveling to Cuba. Curiously, Oswald planned for his future together with Marina while he still harbored thoughts of fighting for Castro.

Ruth Paine’s husband, Michael Paine, in an interview with PBS, aired on Frontline in 1993, remarked he found Oswald, prone on the living room floor, watching a football game on television Sunday afternoon that weekend. Paine remarked, “...I thought, what a fine little revolutionary we have here being snookered into the new opiate of the people, football.” Oswald told Marina that weekend he hoped to find an apartment by Christmas and did not want Ruth to know their future address. Marina said she could not return Ruth's kindness with such harsh treatment, but Oswald had no problem with such ungrateful behavior.

On Thursday, November 14, Oswald talked to Marina during his daily after-work phone call. Marina asked him not to come out to Irving at the weekend because Ruth Paine was having a birthday party for her little girl on Saturday and Marina, concerned about the appearance of hospitality abuse, thought Lee should stay in Dallas. Later that weekend, Marina, in a moment of regret for Oswald's exile, asked Ruth Paine to call his rooming house. Ruth dialed the number and asked to speak to Lee Oswald. The voice on the other end reported that no Lee Oswald lived there. Ruth repeated the number Oswald had provided and the voice answered in the affirmative, the number was correct, but no Lee Oswald was there. Oswald called Marina during lunch on Monday, November 18. He was shocked and furious when Marina related to him Ruth's attempt to reach him by phone the day before. He admitted to Marina living under an assumed name out of fear of the FBI but, in a moment of fury, he hung up. Oswald called back later that evening but Marina, on the wrong end of a flood of verbal abuse, was not receptive, she slammed the phone down on its cradle.

Texas School Book Depository (L) overlooking Elm Street

President Kennedy Visits Dallas

The conspiracy community, for half a decade, suggested that Lee Harvey Oswald, CIA agent, Mafia hit man, KGB agent, pro-Castro revolutionary, or paid assassin of the military-industrial complex killed John F. Kennedy as part of a bigger plot to overthrow the government of the United States. Some contend Oswald obtained work at the Texas School Book Depository for the expressed purpose of assassination. This point becomes the problematic factor surrounding Lee Harvey Oswald. Oswald, a useless megalomaniac, an abusive husband, and social misfit who failed at several previous working opportunities received his employ at the TSBD through the inquiry of Ruth Paine over coffee with neighbors. Hardly the stuff of sophisticated international intrigue.

Kennedy's trip to Dallas arose out of political necessity to repair the fragmented Democratic party in Texas. Kennedy met with Vice President Johnson and Texas Governor John Connally on June 5, 1963, and all agreed on a late November time frame for the president's visit. Kennedy, whenever possible, preferred to ride in an open car to allow as many people as possible to see and be seen by the president.

The overarching consideration during Kennedy's presidency became a policy of route planning through large cities with high rise buildings, wide streets, and correspondingly large crowds. The Secret Service

planned the Dallas motorcade according to this procedure.

Responsibility for advance preparations for President Kennedy's visit to Dallas became the primary duties of two Secret Service agents: Special Agent Winston G. Lawson, a member of the White House detail, and Forrest V. Sorrels, special agent in charge of the Dallas office. Both agents were advised of the trip on November 4, 1963. A key element in the initial planning of the Dallas visit remained the selection of a luncheon site following the motorcade through the city. Three potential sites presented possibilities and presidential special assistant, Kenneth O'Donnell, selected the Dallas Trade Mart as the site of the fund-raising luncheon on November 14, eight days before the assassination.

Lawson and Sorrels met with Dallas Police Chief, Jesse Curry, and other city officials to plan the route through Dallas and the Secret Service agents informed the city officials of the approved route on November 18. On November 19, the Dallas Times-Herald newspaper printed the route in their afternoon paper and, the following day, November 20, a front-page article displayed the motorcade map and included the report that "the motorcade will move slowly through Dallas to give crowds a good view of President Kennedy and his wife." The route selection, passage directly in front of the Texas School Book Depository, resulted from the decision to include the Trade Mart in the itinerary and to provide the most direct route via the Stemmons Freeway not to bring the president under the sights of Lee Harvey Oswald.